The Newsroom

An Interview with Kim Dorland

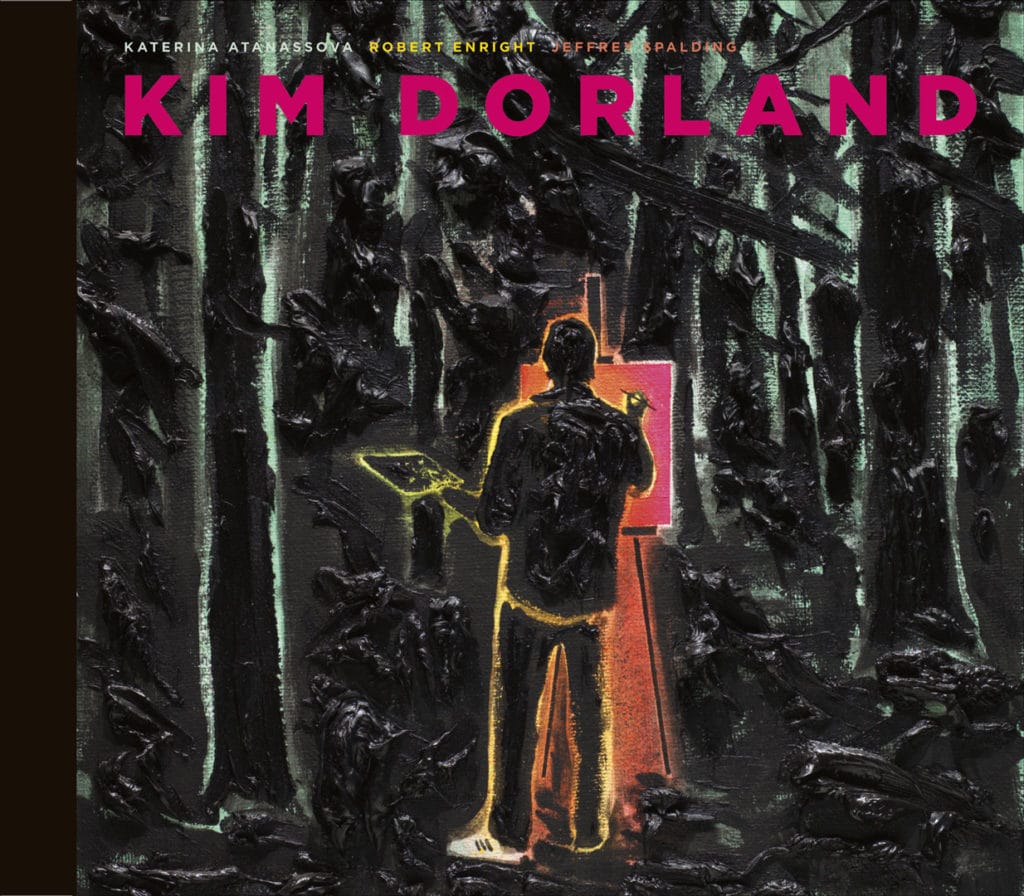

For several years now, art critic Robert Enright and Kim Dorland have engaged in an ongoing dialogue about Dorland’s work, and art in general. This interview is an edited collage of four conversations. Check out Kim Dorland for a more complete version.

In choosing paintings for this book, you’ve had a chance to go back through your earlier work. What have you learned?

What struck me was my fearlessness. I didn’t expect anything at that point, so there was a youthful energy. Now that I’ve been painting for a long time, I’m better at it, and earnestness has been replaced with sophistication. There was also an interesting clumsiness to the work. On the other side, things haven’t changed at all. The colour sense is still there and the material is definitely there, though what I call thick is definitely a lot different now. In a weird way, the work I have been doing since the McMichael exhibition is actually more like my old painting.

You have made a lot of zombie paintings—a number literally have “zombie” in their titles. I know some of them muse on what it’s like to be a father. But I’m interested in the range of responses that you generate out of your own psyche in doing those paintings with isolated, weird figures wandering through nocturnal spaces.

I have always been a melancholy person, and it is something I battle. But those zombie paintings were a response to looking around me and noticing people. There is this new Damon Albarn album in which the title song talks about our being “everyday robots on our phones.” So there is this distance, and even though we live in a very congested way, we are still separated and alone. I’m not trying to make a comment on technology, but I see a pervasive sense of sadness around me. So beyond the fact that I am a huge Walking Dead fan, I thought the zombies were a way to make a comment about contemporary life.

You have some pretty unconventional animals in your painting. You push nature in directions that are not natural.

I guess that has always been caused by my healthy fear of nature. I’m not an outdoorsman, and even as I get older and more confident, I’m still an observer of nature and not a participant. That was my way of making those animals as distant and otherworldly as I could possibly make them.

Sometimes they’re frightening, and at others they are almost exquisite.

It’s total reverence. I am in awe of nature but I’m also scared to death of it.

When did you first get involved with landscape painting?

We would spend a month or two every year in my wife’s family cabin in northern Saskatchewan. I don’t go deep into the landscape, or hunt, or anything like that. But every time I was there, I would take hundreds of photographs and bring back the experience with me. There’s a painting from 2007 of the northern lights that is a direct experience in nature. I would say that 90 percent of the landscapes I have painted have some kind of interruption or interference. For me it was always about shining a light on that. The McMichael show was an anomaly because it was about interacting with the permanent collection, which I wanted to do in a way that paid respect to the artists.

What is it about Thomson that you respond to in such a passionate way?

I am very attracted to his myth. He wasn’t the most talented or naturally gifted member of the Group. I think Lawren Harris was more elegantly talented, but Thomson was self-taught and he was rough. He got better and better and better through the work, which is how I proceed. He was also a brilliant colourist, and the way he used material was perfect.