The Newsroom

Excerpt: “Walking to Camelot”

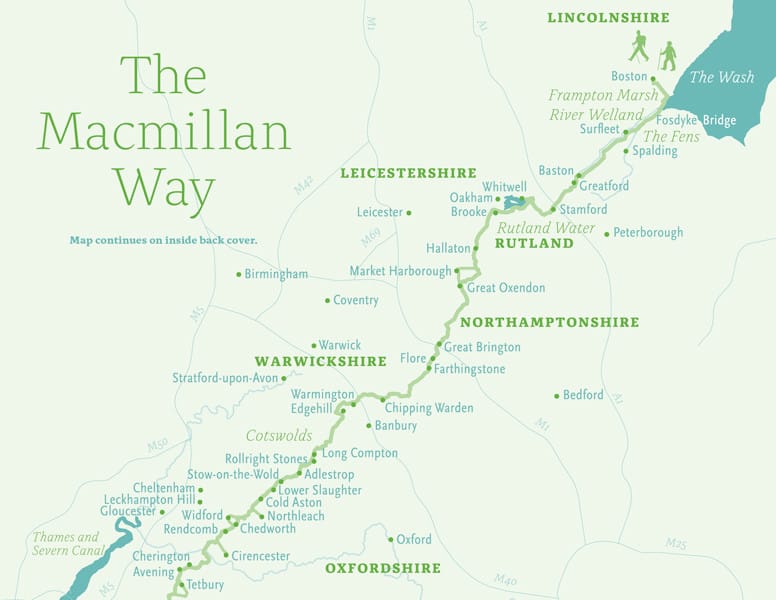

Walking to Camelot: A Pilgrimage through the Heart of Rural England is a charming 300-mile romp through farm, field, and English history, with two crazy Canadians as our guides.

Chapter Six

Heart of the Cotswolds

The leaves of the garlic plants are spear-shaped and slender, and release a scent that seduces one to pluck and suck. This wild garlic is a species native to Britain and grows prolifically in ancient woodland. Garlic contains allicin, which is both antifungal and antibacterial. And of course chopped-up garlic adds real zest to salads and soup. After munching my fill I lope awkwardly along the winding path to try and catch up to Karl. I am wracked with momentary guilt, for I have trespassed off the path to enjoy the bounty of this private wood.

The owner has every right to complain about us walkers. Perhaps Madonna has a point in wanting to maintain her estate unsullied by muddy-booted ramblers. History records that even the most passionate democrats have ranted against public footpaths crossing their land. For instance, E.M. Forster, author of A Passage to India, purchased a little wood in Surrey, not far from London, but was tortured by the fact that it was “intersected, blast it, by a public footpath.” This literary champion of the common man morphed into a strident property owner, on the prowl against anyone who plucked his blackberries, his bluebells, his hazelnuts. Forster derided the prevailing economic system that in his view caused him such conflict in his soul between empathy for the rights of the common man to access woodland and the desire of the owner to protect that land from public despoliation.

This introspection leads me to realize that the linear walk we have been taking, now well into our second week, is completely different from loop walks; it really is a journey in which one loses oneself to the landscape of history. We have passed through the Narnia wardrobe portal. The modern world is a thousand miles away. Thanks to Karl’s problems with his mobile phone, we are deliciously cut off from the cares of daily life, emails left behind. Though I look forward to talking to my wife every week or so, I do not wish to hear about the mundane issues of family and household which she is facing. Selfish me.

The Cotswolds are classed as one of the world’s areas of outstanding natural beauty. The name derives from the Saxon cote, a sheepfold, and wold, meaning a bare hill. The Cotswolds defines that range of hills in west central England some twenty-five miles across and ninety miles long, centred in Gloucestershire but including parts of Wiltshire, Somerset, Worcestershire, Warwickshire, and Oxfordshire. Sheep are the economic engine in the history of the Cotswolds. The splendid towns, fine churches, and magnificent honey-hued mansions were all paid for by wool profits from an era when England ruled the world of cloth manufacturing. In Westminster, the lord chancellor still sits on the Woolsack.

Huge flocks of sheep used to be driven from Wales, and it could take three hours or more for them to pass through towns like Stow and Banbury. By the fourteenth century, Europeans recognized the best wool as being English—and in England, the prime wool was Cotswold. After shearing, Cotswold wool was usually sent to ports like Southampton, from where it was shipped to the Continent. Local merchants grew wealthy and gave some of that wealth to the building of parish churches and other important buildings. A Cotswold epitaph for one such merchant reads:

I praise God and ever shall

It is the sheep hath paid for all.

After the demise of the woollen industry, this region of rolling and folding hills and coombs, of quiet villages and tiny lanes, quickly became a mecca for tourists and the retiring affluent. Horse riding, breeding, and racing are all the rage. The pubs overflow with well-dressed, tweedy locals and weekending Londoners.

The Cotswolds are home to a star-studded roster—Prince Charles, Prime Minister David Cameron, Arab sheikhs, industrial barons, and film stars such as Kate Winslet, Elizabeth Hurley, and Hugh Grant, to name but a few. Don’t expect them to participate in ferret-racing, cheese-rolling, or nettle-eating contests. But by and large, they respect the long-time country residents and traditions. Of course, appearances in this country are invariably deceiving: the farmer’s wife down the lane might well have a degree in nuclear physics; her unshaven, eccentric neighbour puttering about his greenhouse in mismatched tweeds and smoking the briar pipe—meet the former ambassador to Iran.

Walking to Camelot by John A. Cherrington is in stores now!