The Newsroom

Excerpt: “Out North”

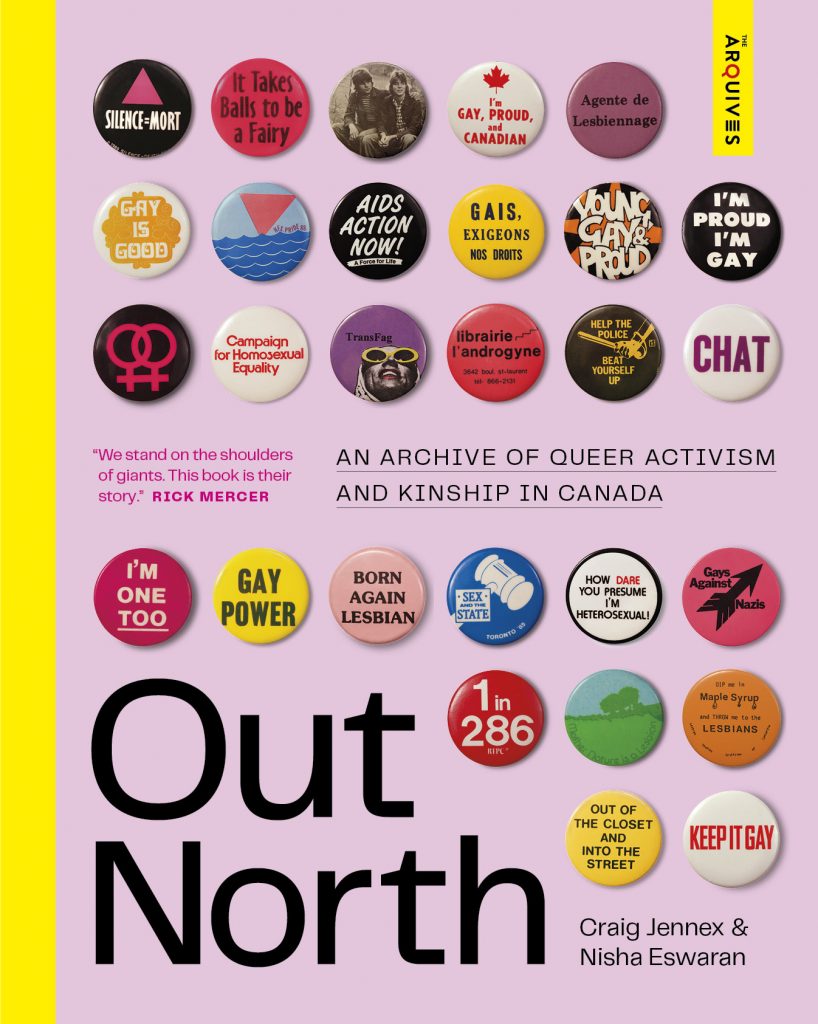

LGBT Pride Month occurs in most North American cities in June to recognize the impact LGBTQ2+ people have had in the world. To celebrate we are sharing the introduction to the newly released book by Craig Jennex and Nisha Eswaran, Out North: An Archive of Queer Activism and Kinship in Canada which is a fascinating and wide-ranging documentation of queer history, activism, and community that examines the vast collection of The ArQuives, the largest independent LGBTQ2+ archives in the world.

Introduction: Memory Work

On December 30, 1977, members of the Metropolitan Toronto Police and the Ontario Provincial Police raided the offices of the Canadian Gay Archives and The Body Politic, one of Canada’s first and most prominent gay publications. Police seized twelve boxes of the Archives’ holdings in order to charge the officers of Pink Triangle Press (the not-for-profit collective formed in 1976 to incorporate The Body Politic and the archival project) with the crime of “distribut[ing] immoral, indecent or scurrilous material.” The raid is only part of a long history of police raids that targeted gay, lesbian, and trans communities. In “Stashing the Evidence,” an essay he wrote in 1979 for The Body Politic following the raids, gay liberationist and AIDS activist Rick Bébout recounts the difficulties and the pleasures of archiving queer history under homophobic and hostile political conditions. That essay is the inspiration for the archival work we do in this book. While there have been many social and legal shifts in Canada since Bébout wrote “Stashing the Evidence,” memory work—the act of remembering, holding on to, and cherishing prior experiences, relationships, and possibilities—remains a crucial part of queer life in Canada.

Routinely erased from conventional or state-sanctioned modes of memorialization, queer people have built archives in myriad ways, collecting both tangible and intangible records of queer life: stories, writing, photographs, ephemera, and so much more. Such records are crucial, particularly as queer life is rapidly changing in Canada; as more of us are recognized by the state through the legalization of gay marriage and many of us see ourselves better represented in increasingly “diverse” forms of media, archives of the queer past remain critical. Indeed, many of us retain complex emotional attachments to the forms of friendship, solidarity, sexual freedom, and protest that preceded state and media recognition of certain manifestations of queer life. Both of us (the authors) remember, for instance, how pivotal archival records were to our respective comings of age as queer individuals: materials that evidenced queer people convening, organizing, dancing, protesting, and building families gave us a sense of history and lineage—an inheritance of a queer past that remains sacrosanct, the impetus for our work here—and a sense of possibility, of a future where queer sexual desires, practices, and communities are alive and flourishing. Our motivation in writing this book is to linger in the emotional attachments we have to such archives and to ask how our connections to the past enable and enliven queer life now.

This book takes as its starting point the vast collection of The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives (formerly known as the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives). Formed in Toronto in 1973, the organization has grown to be the largest independent LGBTQ2+ archive in the world. We aim to bring the ArQuives’ diverse collection of historical photographs, posters, writing, artwork, and ephemera to a broader audience. For us, these materials are exciting and enlivening because of the complicated ways they speak to multiple queer pasts while simultaneously articulating a queer future yet to come. In reproducing and collectively returning to these historical materials, we have considered how the ArQuives’ collection speaks to both the histories and the future possibilities of queer life in Canada.

Certain narratives of queer Canada are taken as fact—for instance, the idea that we, as a nation, have steadily marched toward progress, tolerance, and acceptance since the so-called decriminalization of homosexuality in 1969. The legalization of gay marriage in 2005, for example, is regarded as evidence of a linear progress through which queer people are recognized and accepted by the state. We recognize the power of this narrative and the comfort that it carries, but part of our interest in this book is to move away from this narrative of progress—a narrative we perceive as too simple, too linear, too easy—and return to earlier moments and the materials created therein that hold unrealized potential for the present.

While we do not deny that queer life changed rapidly in Canada over the latter half of the twentieth century, we aim in this book to consider some of the unofficial records of queer life evidenced in the collection at the ArQuives. What does this collection reveal about the hidden histories of queerness in Canada, and how do these stories challenge or add to the official narratives of progress? Which alternative forms of queer resistance and pleasure were at play in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, and how do they inflect queer life now? Whose work and life stories are missing from the collection, and, in addressing these absences, can we better understand our collective queer history? The purpose of this book is to consider these many questions through the ArQuives’ collection and to build forms of kinship with individuals and movements of the past.