The Newsroom

Excerpt: “Divine Threads” Preface

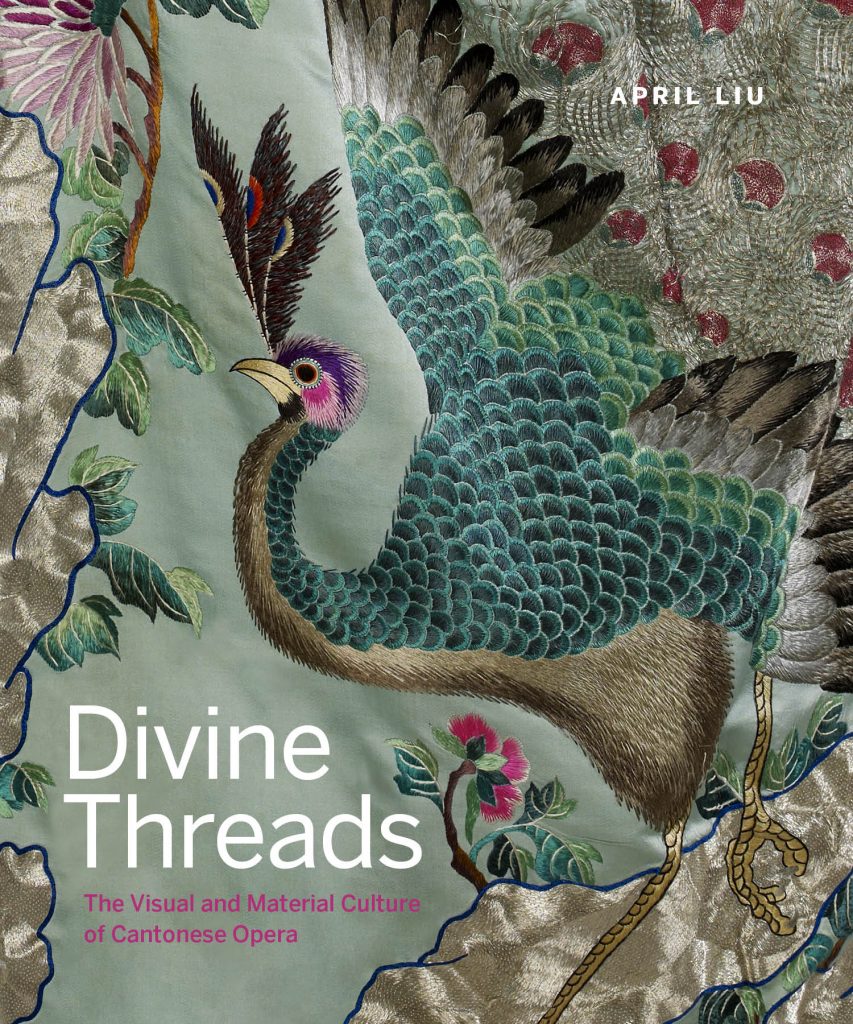

Divine Threads by April Liu shines a light on the visual and material culture of Cantonese opera as a treasure trove of sacred and auspicious images, stories, songs and rituals. Available February 2019.

Preface

by Elizabeth Lominska Johnson, Curator Emerita and Research Fellow at UBC Museum of Anthropology

The collection of antique Cantonese opera materials at the UBC Museum of Anthropology has held its secrets for many years. Of the various specialists who examined the collection in about 1990, only one—the actor and film director Wong Hok-sing—had actually performed in costumes like the oldest ones, and that was at the very beginning of his stage career in the 1920s. At first they appeared to me to be a diverse assemblage of hundreds of costume components with extraordinary features: wing-like appendages, glittering mythical creatures with scales and brilliant green eyes, belts like barrel hoops, headdresses that folded flat and others that were three-dimensional and decorated with feathers, flowing ribbons, or multicoloured pompoms. Some costumes were ornamented with tiny round mirrors and gilt discs, others with sequins, and others with silk embroidery or with gleaming thread made of precious metals. The decorative materials frequently formed symbols rendered on a large scale so that they could be seen by audiences in theatres that did not yet have electric lights. Among these representations were coins, fish, bats, birds, tigers, and butterflies, all familiar from the Chinese symbolic vocabulary, but seemingly incongruous on some of the objects. Shoes and boots often appeared to be almost unwearable, with oddly placed high platforms, or with inner supports forcing the actor onto his or her toes.

There also were the stage fittings and the props: wooden articulated dolls, decapitated papier mâché heads, weapons, banners, and enormous embroidered curtains. The musical instruments bore little resemblance to any I had ever seen: barrel-shaped drums of solid wood in various sizes, bamboo flutes, and stringed instruments, also of bamboo, with the bow caught between their two strings. Most impressive of all were the four big red trunks, solidly built of wood, rawhide, and hand-forged metal, whose painted labels indicated that they had been made in Guangzhou, and whose paper labels testified to their extensive travels.

As the curator responsible for the collection, there was so much I had to learn. Although I had seen performances during my time in Hong Kong as an anthropologist, I had to start with the basics, even to the extent of ascertaining which actor represented a man, which a woman, which a ghost, which a supernatural being. Learning this complex and sophisticated language was more difficult than learning to speak Cantonese! I will always be grateful to those senior specialists who shared their knowledge with me so that we could begin to make sense of this collection, which had come to the museum from the Jin Wah Sing Musical Association, founded in Vancouver’s Chinatown in 1934 and custodian of the materials from sometime around that year. The association had used some of the materials, organized and identified them with handwritten inventory marks, and stored all of them in simple but effective ways so that they survived undamaged—doing so despite the fact that they came to believe these costumes were no longer of value in Cantonese opera’s world of rapidly changing fashion. They were objects that had been left behind, and remained in Canada, for reasons that are still unknown.

This is an abridged excerpt from Divine Threads – available February 2019.