The Newsroom

Excerpt: “Tom Burrows”

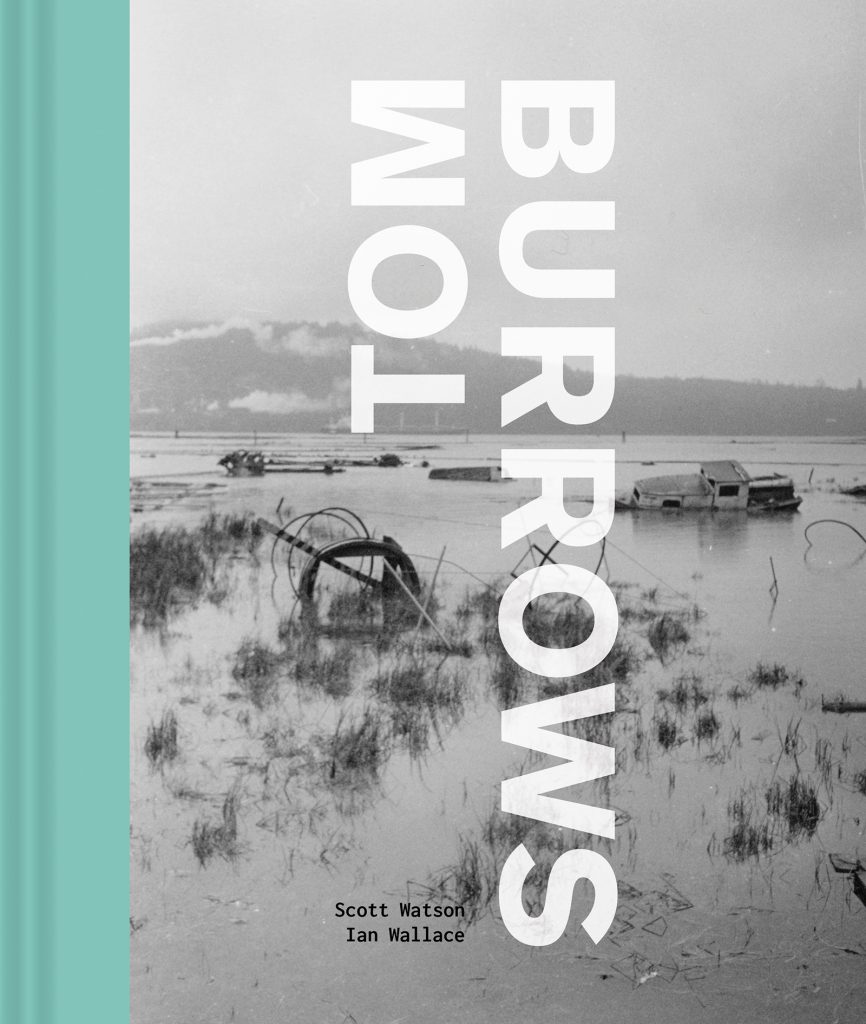

Tom Burrows: Window

Scott Watson

Tom Burrows is known for several disparate but related bodies of work. One has to do with squatting, and involves working with recycled material and houses. The sculptures he made on the Maplewood Mudflats in North Vancouver, which survive only as photographs, and his house on Hornby Island, BC, are icons of their time. During his student days at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London he began a long exploration of polymer resin, which has been the focus of his work since 1989 and has produced many series of translucent panels. There is also a significant group of figurative and allegorical sculptures from the 1970s and 1980s. His work includes an extended critique of contemporary consumer life and the commodification of housing in an attempt to propose not only a different way to live, but also a different way to position art in our lives. His practice has also been a steady, politically motivated engagement with the formal problems of non-objective art. The terms of artistic discourse have changed several times since Burrows embarked on a career as an artist in the late 1960s. His work has negotiated these turns from an independent point of view, grounded in communal and anti-consumerist principles that are ever more pertinent in a world on the precipice of ecological catastrophe and economic collapse.

Burrows describes himself as “a formalist sculptor whose life experiences have at times infused his art production with social narrative (the antithesis of formalism) through the media of architecture, music, painting, performance, photography, video and words, etc. (i.e., life skills).” His website biography directs us to the Wikipedia entry “Formalism (art),” which reminds us that in modern times the question of aesthetic formalism originates in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment, where he distinguishes between the form that is the object of the judgment of taste, and something superfluous to it: “Every form of the objects of sense is either figure (Gestalt) or play (Spiel).”

Seen through this Kantian lens, it would be fair to say that Burrows’s work consists of both “figure” and “play” (the former belonging to formalism, the latter to something else). Of course, by formalism Burrows also means the modernist dicta of fidelity to materials, a consideration of art’s autonomy and the idea that art can have no external referent.

But rather than considering Burrows a formalist at heart, whose other, “playful” production is an antithetical waywardness (from which he returned around 1990), it might be more useful to consider how issues of formalism animate all of this artist’s production. In what ways is the procession of the work itself—its logical or discursive unfolding—punctuated by addresses to a dialectical formalism? How is each work, or body of work, in dialogue with what precedes it and what proceeds from it?

Tom Burrows by Scott Watson and Ian Wallace is available now.